One of the many buzz words in Information Security media today is Zero Trust Networks or ZTN. I like a good acronym as much as the next person (it is easier to type for sure), but it can be hard to understand how you as a CIO can implement a ZTN.

In a sense, a ZTN is what most of us do every day when we walk or drive to an unfamiliar place. Imagine you live in a city or suburb and you’re heading to a new restaurant but you don’t know the neighborhood for this hot new place.

What do you do?

Do you treat this new neighborhood like your own, where you know everyone and know who and what you can trust? No, of course not.

You take some time to get context (in other words, understanding) about this new place to see if you can safely and easily park your car or lock up your bike or walk to it for dinner. You scope out the area to figure out how safe things are in this new environment.

The new bistro has to scope you out, too. Are you safe? Are you someone who can be trusted to pay the bill at the end of the meal? Do you present a threat to them?

You don’t trust the new neighborhood randomly and they don’t trust you right away either.

How does this play out in the information security space?

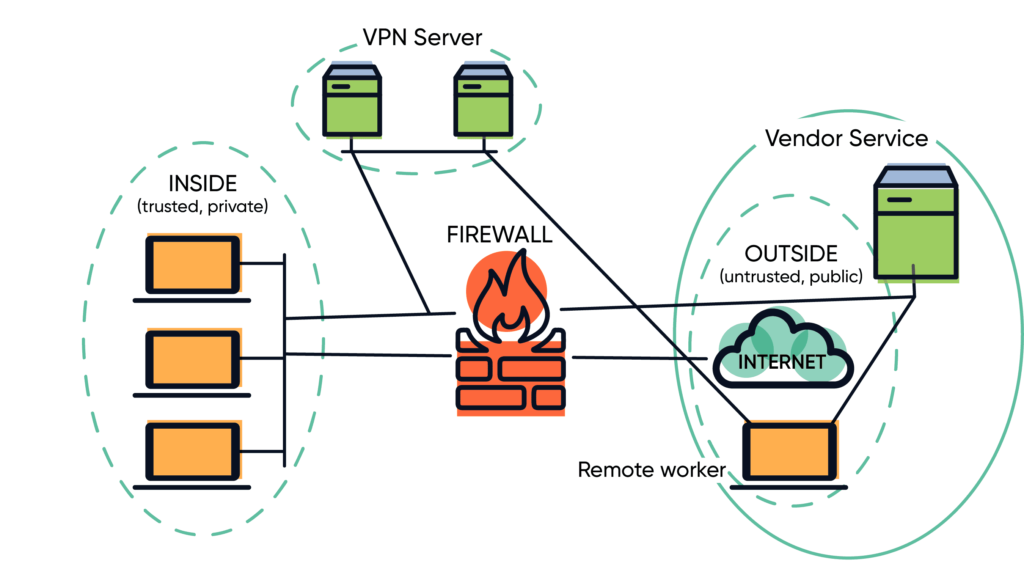

The average company today has multiple vendors that either provide a service or are customers that need access to your network/services. As the CIO you have created a very secure, private network, that typically has a VPN for remote access, and you have vendors providing services or consuming services that are outside of your trusted network. See this basic diagram below:

You can make this diagram more complicated with a DMZ, load balancers, web application firewalls, cloud services, and other things, but this covers the basic environment.

Where are the risks to you and your vendors?

There are three basic threat vectors for modern networks.

- A user may have compromised credentials that can be used in an attack to gain access to your network or your vendor’s network.

- A device may be compromised on your internal network, your vendor’s network, or the remote network. That compromised device can then attack you and/or your vendor(s).

- A software system—like an API—can be compromised and that can impact or infect data on your network, the vendor’s network, or the remote workers.

If you think about the number of devices you have, the number of users, and the number of vendors, you can see how the risk to you and your vendor partners has increased exponentially.

Where does Zero Trust come into this story?

Remember how I started this post by saying you want to go to a cool, new bistro in a neighborhood that is new to you? You (and your vendor partners) need to figure out who you can trust and what is accessing your network. In this case the new bistro is virtually everyone and everything connecting to your network. You have to treat your users, your computer systems, and your vendors as if you do not know them.

How do you do that?

Often this is accomplished with tokens (or a security certificate) that are assigned to a user, or a device, or even a program, after identity and authorization have been determined.

How do you create trust and where does this happen?

Imagine a network configuration that says, “I don’t trust any computer, user, or process until that computer, user, or process has provided credentials (for example, username and password or X.509 certificate) that has been validated (usually with some kind of second factor, an SMS text, authenticator push, or Certificate Authority) as authentic.” Only then does the network confirm that the computer, user, or process is authorized to do what they want to do. Yes, this includes traditionally “trusted” assets, like your own workstations!

The requirement to provide credentials and have them validated and then check for authorization is the basis for Zero Trust. The phrase that is often used is, “Trust nothing, verify everything.”

Because we can’t rely on the IP address of a machine to give us some measure of “identity” (in other words, “I trust this PC because it has our internal IP address”), the machines have to be validated. Typically this validation is with a certificate that is pushed out to the device from a centralized Certificate Authority. There are solutions that automate this process and can provide context before issuing a certificate to a device. Context in this case means, “Have I seen this PC before? Do I recognize the MAC address, serial number, or does it have an IP address I recognize?” The more context you have about a device, the more confidence you have that the device can be trusted. Keep in mind, the trust extended to that device is for that session only, or for a predetermined length of time.

Because we can’t rely on the user to provide just a username and password to prove that they are who they say they are, users have to be validated twice. Usually they identify with a username and password, then we confirm their identity a second time with some other method (an SMS or an authorization application like Duo, Microsoft Authenticator, or others). This multi-factor authentication (MFA) helps provide a level of trust that the person is who they say they are. Just like with the device, the authentication of the users is for that session only and the user will have to re-authenticate once they disconnect or end the session.

As your security program matures you can also verify the software or applications that are running on your systems. Here you would most likely have lists of the applications that you trust and you have a hash value of the executables to make sure that the application has not been modified. This can be a bit complicated, but it is possible.

The main takeaway from this blog is that Zero Trust means—as the name implies—that you don’t trust anyone without some method (or methods) of authentication. For those of you thinking strategically, you might want to hold off on upgrading your VPN this budget year or next, and think instead of a Zero Trust solution for your remote work force.

Need more help with your cyber defense? Contact the CBTS cybersecurity team today.

More from CBTS Consulting CISO John Bruggeman:

What is Cyber Insurance and do I need it?

What do new TSA requirements mean for the security of your critical infrastructure?

How do you ensure the security of your supply chain?

Can you be ransomware-proof? Is that even possible?

Getting ransomware-proof, continued: CIS controls for medium-size organizations

Improve your cybersecurity defense with centralized logging

Improve your cybersecurity defense with centralized logging, continued: A deeper dive!